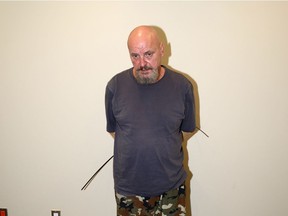

Basil Borutski guilty on three counts of murder in Ottawa Valley rampage

Article content

OTTAWA - An OPP detective spent a mere five minutes in an interrogation room with Basil Borutski before the killer admitted to the systematic murders of Carol Culleton, Anastasia Kuzyk and Nathalie Warmerdam, calling the killings his own brand of “justice.”

The jury in his triple-murder trial began deliberating on Wednesday before finding Borutski, 60, guilty on two counts of first-degree murder and one count of second-degree murder on Friday.

The five women and six men of the jury believed the Crown’s contention Borutski had his mind set on murder as he carried out the Sept. 22, 2015 rampage through Renfrew County that left his three former romantic partners dead.

Prosecutors Jeffery Richardson and Julie Scott used 17 days of testimony — through seven weeks of a trial originally scheduled to span 17 weeks — to call 45 witnesses to give evidence, the bulk of it unchallenged and uncontested in court.

Borutski did not hire a lawyer and mounted no defence while acting as his own counsel from the prisoner’s box, his eyes frequently closed and head resting on the glass throughout the trial. He called no witnesses and did not testify in his own defence.

[related_links /]

Borutski broke his trial-long silence during a break Wednesday, with the jury excused, as he questioned Justice Robert Maranger on “the very basis of a fair trial."

He complained about missing his opportunity to address the jury in his own defence, which passed Tuesday after the Crown concluded its closing arguments, and Borutski stayed silent when his turn came to enter a defence.

“Have I missed that?” he asked Maranger Wednesday. “I was waiting for that … You did say that, I’m not lying.”

Maranger replied he afforded Borutski “with exact precision” every opportunity to call evidence, testify or make a statement on his behalf.

The Crown and amicus James Foord agreed Maranger had been consistent throughout the trial in affording Borutski that opportunity, and the chance to challenge testimony from each Crown witness.

“I have no pencil, no paper and I can’t take notes,” Borutski complained. “And I’m supposed to be able to represent myself?"

He accused Maranger of misrepresenting to the jury the reason why he had not spoken in court nor hired a lawyer.

“That’s a lie and you’re part of it,” Borutski said, without elaborating.

The judge dismissed the complaint and ordered the jury to return to the courtroom.

Borutski had refused to participate in pre-trial hearings in Ottawa, or in the trial’s original jurisdiction in Renfrew County. Details of those proceedings, which the jury did not hear and remained under publication ban until Wednesday, included a judge’s order for a psychiatric assessment.

Borutski did not participate in the psychiatric evaluation, and a verdict of Not Criminally Responsible (NCR) was not among the options available to the jury.

The jury was told to weigh the evidence on each charge to find Borutski guilty of first-degree murder, second-degree murder, manslaughter, or not guilty.

There was never any doubt — among investigators, prosecutors, and many in and around the Wilno community — that it was Borutski who beat and strangled Culleton to death at her Kamaniskeg Lake cottage that morning before driving her car to Wilno, where he shot and killed Kuzyk, then to Warmerdam’s Foymount Road farmhouse, where he shot and killed her, too, with a shotgun.

Borutski had been romantically involved over the years with all three of his victims, and had a history of domestic violence against both Kuzyk and Warmerdam.

Borutski was attempting to rekindle an old flame with Culleton, who broke off their casual relationship and tried to distance herself from Borutski in the days and weeks leading to her death. She was the first of his victims to die that day.

The Crown framed the case not as a “Whodunnit?” but as a “Whydunnit?”

Borutski’s apparent motive for the killings, the Crown established in the trial’s early days, was out of twisted revenge for a life spent under the belief he had been wronged by “the system,” as he would so often complain to the people he knew.

Borutski carried long-simmering grudges with him to the day of the killings and beyond, as the jury saw in his confession, told over the course of a five-hour-long police interview the morning after the murders.

The videotaped interrogation at the OPP’s Pembroke detachment by Det. Caley O’Neill would become the centrepiece of the Crown’s considerable evidence against Borutski.

Early in the confession, over coffee and doughnuts, Borutski calmly told the officer he'd been arrested “for killing, not murder.”

He went on to tell a long and sordid backstory, complaining at length about his perceived treatment by police and the courts through different episodes in his life, before coldly detailing each of the killings, claiming, “They were guilty … I was innocent.”

He cited his own reading of the Ten Commandments, which he believed would provide vindication, saying he consulted his personal Bible on the eve of the murders.

That same night, as neighbours testified in his trial, Borutski angrily ranted about women as “sluts and whores” and spoke at length “about the difference between killing and murder.” He told his neighbours, who noticed he seemed depressed, he had just broken up with his girlfriend at her cottage after finding her cheating on him. He had in fact just returned from angrily confronting Culleton at the cottage.

She had gone to the property that Monday to keep an appraisal appointment with a realtor, hoping to sell the cottage after just celebrating her retirement from the federal public service that weekend.

She had also told Borutski a day earlier she had recently renewed a relationship with a former boyfriend, and no longer wanted anything to do with Borutski.

The Crown brought evidence from witnesses in the community who recalled conversations with Borutski and with his victims, and also produced a handwritten letter Borutski mailed to Culleton the day before killing her.

Key Crown evidence came in the form of a lengthy text message exchange between Culleton and Borutski, beginning as she attempted to break off the relationship, and continuing through a furious days-long text tirade. Borutski ended by saying, “I will endure the betrayal of yet another false friend … karma will take over.”

Investigators found forensic evidence at each of the scenes Borutski visited that day. He left his wallet in a car console at Culleton’s cottage, a palm print on the front door frame of Kuzyk’s house, and he was seen by security cameras and an eyewitness at Warmerdam’s farmhouse.

Blood on his clothing matched that of both Culleton and Warmerdam. Shells recovered from the final two murder scenes matched the J.C. Higgins Model 20 pump-action shotgun he used that day.

Police found the weapon lying in the long grass by following directions Borutski gave them during his surrender in a Kinburn field hours after the killing spree.

Three days later, another handwritten letter arrived to the Pembroke office of his former parole officer: “Judge not lest ye be judged. Now ye will be judged by me,” he wrote.

“I can’t take it any more — I’m getting out and I’m taking as many that have abused me as possible with me. JUSTICE.”

Borutski believed he had been wrongfully accused in earlier episodes of domestic violence against his wife, Mary Ann Mask, throughout their tumultuous 26-year marriage.

Though he believed his tarnished reputation in the rural community contributed to his frequent run-ins with law enforcement and the courts, he told police he never thought of killing Mask that day.

In a portion of the confession video redacted from the jury, Borutski outlined a vague plan to kill another man in White Lake, though he didn’t know his name. He also said he would have tried to shoot and kill any police officer who tried to stop him.

He claimed during his confession he was “maliciously prosecuted” and jailed in 2012 for threatening to hang Warmerdam’s teenage son Adrian, who would later testify as an eyewitness to his mother’s murder. Borutski also claimed Kuzyk “lied in court” in 2014 when he was convicted for choking and beating her one night in a rage.

He had refused to sign a court order to stay away from Kuzyk upon his most recent release from jail, nine months before the killings.

Warmerdam wore a panic button around her neck as a direct line to police, and kept it on her bedpost out of fear of Borutski’s return after their relationship ended with Borutski’s arrest in July 2012.

Warmerdam also kept a shotgun stowed within reach under her bed.

Before his July 2012 arrest, Borutski, who kept a hunt camp near his hometown of Round Lake Centre, was granted a firearms possession and acquisition licence. At some point, he would later claim, he came upon a rusted old shotgun in a salvage yard. Following his domestic violence convictions, which carried a lifetime weapons ban, he stowed the gun in a bush.

Suffering from what he saw as past betrayals, and with Culleton rejecting his latest advances, Borutski turned his mind to murder in the days leading to the killing spree, Richardson said.

Making its case for the elements of planning and deliberation required for a first-degree murder conviction, the Crown said Borutski planned to kill all three women, “and he executed his plan perfectly.”

ahelmer@postmedia.com

Twitter.com/helmera